The Emacs Window Management Almanac

Window management in Emacs gets a bad rap.

Some of this is deserved, but mostly this is a consequence of combining a very flexible and granular layout system with rather coarse controls. This leaves the door open to creating and using tools for handling windows that employ and provide better metaphors and affordances.

As someone who’s spent an unnecessary amount of time trying different approaches to window management in Emacs over the decades, I decided to summarize them here. Almanac might be overstating it a bit – this is a primer to and a collection of window management resources and tips.

Window management in Emacs bleeds into buffer, state, workspace and frame management, so it’s difficult to contain the scope of any article that aims to be comprehensive. To that end,

- this write-up assumes that you’ve finished at least the Emacs tutorial and are familiar with basic Emacs terminology (what’s a buffer, window and a frame) and with window actions: splitting windows, deleting them or deleting other windows, and switching focus.

- There are only a few brief mentions of tabs, as they are primarily a tool for workspace management, as opposed to window management.

- I’m focusing on window/buffer management within an Emacs frame. Many of the below tools work across frames just as well, but you’ll have to find the right switches to flip to enable cross-frame support.

- Finally, this is more my almanac than a wiki: It covers only tools or ideas I’ve personally explored over the years, with brief mentions of potentially useful packages that I haven’t tried. Any omissions are not value judgments, please let me know if I miss something useful.

At some point this transitions from listing well known tools to tips, then hacks, and finally unvarnished opinions. It’s front-loaded: the first chunk of the write-up gives you a 70% solution. If you are new to Emacs, feel free to stop at 30%. If you are an old hand, feel free to skip the first 30%. It also lists substitutes: several ways to do the same things, so you can pick just one method and ignore the rest. Things get progressively more opinionated and idiosyncratic in the second half.

If you are reading this in the future, this write-up is probably out of date. The Emacs core is very stable, but the package ecosystem tends to drift around as packages are developed and abandoned. The built-in solutions will still be around, but there are no guarantees on the third-party packages! That said, the longer a package has been around the more likely it’s going to stick around in a functional state – even if only as a frozen entry in the Emacs Orphanage.

As new ideas emerge, there will be new approaches to window management that aren’t covered here. These innovations don’t need to happen in the Emacs sphere – Emacs likes to steal reinvent ideas that originate elsewhere, much as other applications rediscover ideas that Emacs introduced in the 1990s. So this topic might be worth revisiting afresh in a few years.

What we mean by “window management”

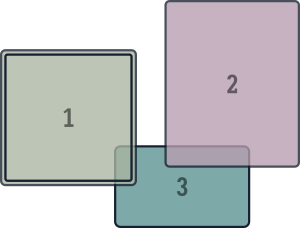

Emacs separates the idea of a window (a “viewport” or “pane” in the frame) from the buffer, a contiguous chunk of text that may or may not be the contents of a file. These concepts are usually fused in IDEs and text editors – this reduces the cognitive load of using the application, but closes the door on more flexible behavior and free-form arrangments. For example, many editors don’t let you have two views of the same file, which is trivial in Emacs. They’re often uncomfortable even with the idea of a dissociated buffer – a buffer that does not represent the (possibly edited) contents of a file. Reified concepts like Emacs’ indirect buffers are completely foreign to them Unfortunately for Emacs, its current design rules out some clever ideas that other editors have implemented. One example of this is the 4coder’s yeetsheet or Dion systems’ views: You can have buffers whose contents are “live” substrings of multiple other buffers, i.e. you can mix and match pieces of buffers. In Emacs the most you can have is indirect buffers, i.e. full “live” copies of a buffer. .

Emacs allows you to do a lot more, but users have to contend with this cognitive cost. New users pay thrice: they have to deal with getting windows into the right places in the frame, getting buffers into the right windows, and they miss out on the upside because they don’t yet realize what this decoupling makes possible. Hopefully this write-up can address two of these costs.

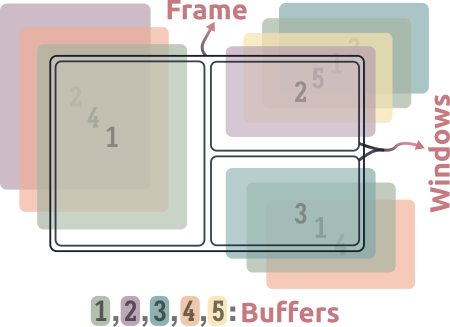

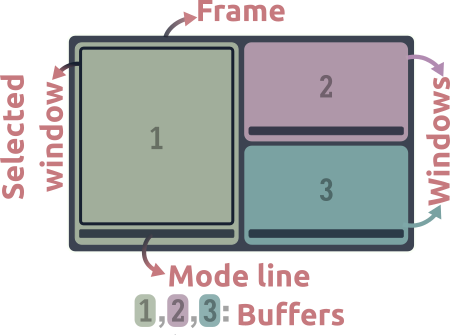

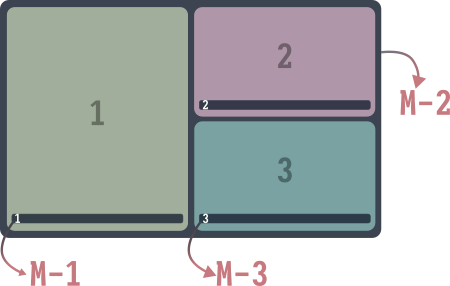

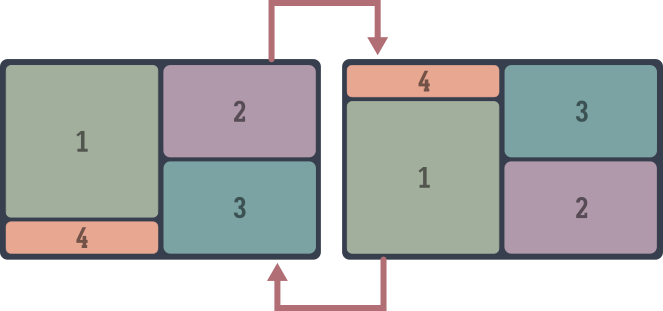

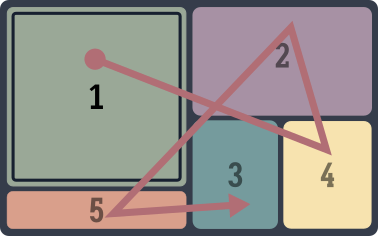

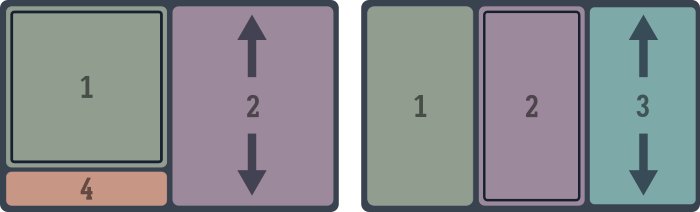

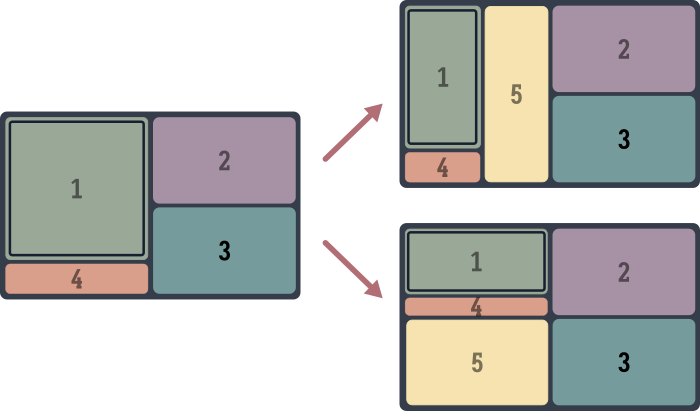

For reference in the rest of this article, here’s a non-exploded schematic of an Emacs frame, with the left window selected:

- Each colored block is a window, the numbers represent buffers being shown in them.

- The active window is the one with a black border.

This article is not about…

Since actions with or on windows in Emacs are primitive, common and unavoidable operations at any level of Emacs usage, this topic is suprisingly subtle, broad and deep, and there’s only so much I can explore in 15,000 words. So we begin with some disambiguation and a narrowing of focus. This article is not about the following things.

Rules for displaying buffers

Emacs keeps popping up windows in the wrong places and destroying my window arrangement!

The situation is… less than ideal. Displaying buffers in the right windows automagically is generally possible but this configuration is involved and requires knowledge of minutiae of the Emacs API, like window-parameters, slots and dedicated windows. the display-buffer API is so involved that describing it takes up a big chunk of the Elisp manual, and even that concludes by saying “just go with it”.

And this is the one aimed at developers using elisp. It’s not even the Emacs user manual!

I mention automatic window management briefly towards the end, but this article is not about reining in the behavior of display-buffer. I recommend Mickey Peterson’s article on demystifying the window manager for this, this video by Protesilaos Stavrou, or the manual if you’ve got the stomach for it.

Window configuration persistence, workspaces or buffer isolation

I want Emacs to group together windows for a given task and persist them across sessions!

Two common factors affecting Emacs use:

- Emacs sessions tend to be long lasting, and

- its gravity pulls users into using it for an increasing number of tasks.

The result is that you end up with hundreds of buffers and start looking for ways to group them, isolate the groups and then preserve them. This is tied to window management, but only in the sense that your arrangement of windows is part of the state you want to preserve. This is a finicky and complex subject, and well beyond the scope of this write-up. Take your pick: between tab-bar, tabspaces, eyebrowse, tab-bookmark, desktop.el, persp-mode.el, perspective, project-tab-groups, beframe and activities.el there is no paucity of projects to help you do this.

Paradigmatic changes to window behavior in Emacs

Why is window placement in Emacs so capricious? Tiling window managers solved this problem ages ago!

Some packages provide all-encompassing, radical solutions to window arrangment and management – essentially, they are window managers for Emacs. For example, Edwina modifies Emacs’ manual window-tree based behavior to enforce a master-and-stack DWM-style auto-tiling layout, with a complete suite of accompanying window management commands. HyControl provides a control panel for window layout actions and can display windows in a uniform grid on the frame, among other features. Apologies for the terse and possibly inaccurate descriptions, I have only brief experience with these. .

In my experience “complete” solutions like these are great when you start using them, but eventually cause more friction than elation. This is the case the more you customize Emacs, as the abstractions they build on top of the Emacs API end up limiting, as opposed to liberating you in the long run.

So what’s left? In this article, we mean window management in the manual and mundane sense: switching window focus, moving buffers around windows, splitting or closing them and so on. Even if you’ve got display-buffer all sorted out and your windows grouped into workspaces, these are the kinds of things you have to do with windows – repeatedly and often – in the course of minute-to-minute, regular editing.

Let’s address a couple of common concerns and dismissals before we get started in earnest.

The two-window perspective

This palaver is pointless, I need two windows at most.

Correction: You need at most two windows at a time. And that’s partly because corralling windows is a mess in Emacs. Except during bursts of writing or coding, chances are you need easy access to more than one buffer – for reference material or look-ups, search and compilation results, file access, shells and REPLs, table of contents and so on. Whether these are on screen in windows all the time or easily displayed on demand is a matter of screen size and preference, but both involve interacting with windows and buffers manually. Both approaches are thus under the purview of “window management”, and addressed in this article.

The pointer prescription

Just use the mouse? This isn’t even an issue in most software.

The mouse is indeed the most natural way to navigate windows. Without stepping into contentious discussions on economy of motion, RSI trouble or personal preferences, the main problem with the mouse approach is that the lack of a learning curve (relative to the keyboard) is balanced by the lack of expressivity (relative to the keyboard).

Even so, you can squeeze a lot more expressivity out of the mouse in Emacs than you can in most other applications The ACME editor might be the most notable exception. . I use the mouse for managing windows in Emacs often – but only in certain contexts, see Mousing around.

Warming up

Our appetizer: a short run-through of the most popular and commonly recommended window management options. These cover changing the focused window, moving windows around and undoing oopsies, with a side of buffer management and bespoke window actions This is the part you can skip if you’ve been around the block a few times. Jump ahead to digging in. .

other-window and the “next window” (built-in)

other-window offers: selecting windows

The other-window (C-x o) command is the baseline window switching experience. It’s what the Emacs tutorial teaches you, and it works well enough when you have a small number of windows:

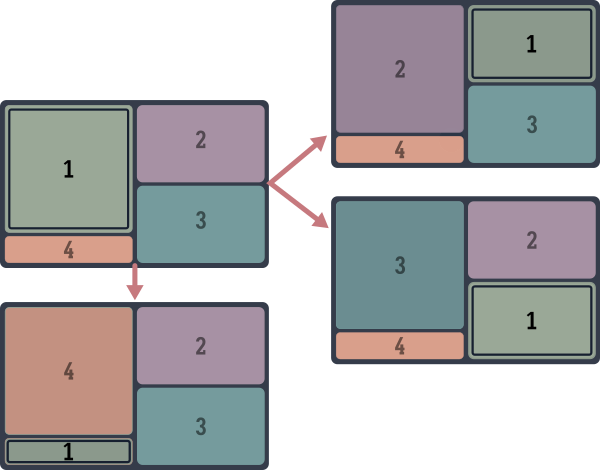

The window selection cycles (roughly) clockwise across the frame. The advantage of this approach is simplicity – it’s a single command and keybinding. As you might expect or have experienced, it takes progressively more invocations to get somewhere as you accumulate more windows, and works best if you rarely have more than two windows showing at once.

Basic

Basic other-window tips and tweaks

- It’s possibly one of the most used Emacs commands – bind it to a more convenient key like

M-o. - You can use digit arguments to skip windows or to cycle windows backwards.

M-3 M-owill select three windows ahead, andM-- M-2 M-otwo windows back. Unfortunately this requires a visual understanding of the order in which the cycling happens. It’s not obvious which window is three windows away in more complex window layouts. - Turn on

repeat-mode(M-x repeat-mode) to continue switching windows with justoand (backwards)O.C-x o o o o...orM-o o o o...is faster thanC-x o C-x o C-x o....

other-window hacks

You can make other-window skip over a window by setting its no-other-window window parameter. A window parameter is a property of Emacs’ window data structure, and there are Elisp functions to set them. This is usually something you’d specify in advance for certain classes of buffers in display-buffer-alist, not a manual toggle. If you’ve ever wondered why other-window does not select the windows of fancy file-manager listings (like dired-sidebar or dirvish-side), this is it.

If you only ever have two windows showing in Emacs, or if you don’t mind punching o a few extra times, you can stop here. The rest is just varying degrees of optimization applied to a problem that you probably (and perhaps realistically) don’t believe needs solving!

Understanding the “next window”

Understanding the “next window”

The “next window” is the window that other-window selects, usually clockwise from the current one. You can access it in elisp by calling the next-window function. With daily usage, you automatically develop intuition for the clockwise ordering of windows in an Emacs frame – in the sense that you know instead of think. This is handy, because the notion of the next window is useful for more than just window selection. There are better ways to select windows, or there wouldn’t be much to this write-up! The next window is the default window for commands that operate in another window, like scroll-other-window. See Do you need to switch windows?

windmove (built-in)

windmove offers: selecting windows, swapping buffers in windows, deleting them

Windmove is a built-in Emacs library for moving the focus across windows – and for moving buffers across windows – by direction. Vim users, this is what you expected. evil-mode users, you already use Windmove, you just don’t know it.

If other-window is the alt-tab of Emacs, Windmove is the tiling window manager equivalent. It makes the spatial arrangement of windows in the frame relevant to the selection, which I imagine is the most natural way to do it short of using the mouse.

Using Windmove is simple: bind windmove-left (resp -right, -up and -down) to a modifier or leader key plus whatever keys you associate with directions: WASD, HJKL or the arrow keys perhaps.

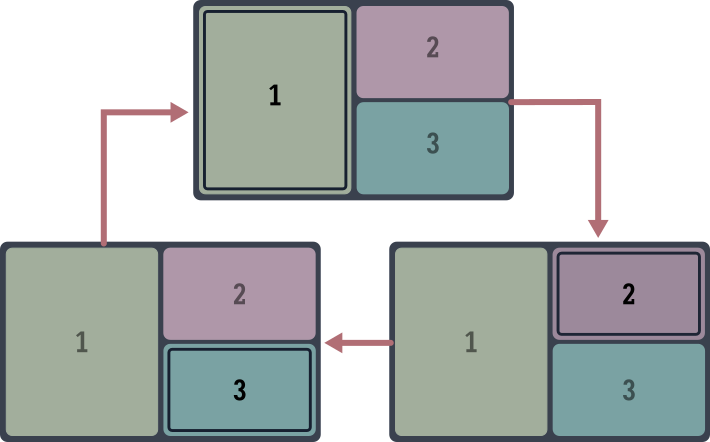

The fork: movement to the right in this schematic depends on what window is exactly to the right of the cursor. Calling windmove-right from near the top of buffer 1 moves the focus to buffer 2, starting near the bottom moves the focus to 3.

You can also swap the buffers of windows directionally with Windmove, a handy way of rearranging windows on the frame

Again, Windmove is how evil-mode does this.

. The relevant commands are windmove-swap-states-left, -right, -up and -down.

Note that the focus moves along with the buffer when you do this.

There’s more yet to Windmove, you can delete the window next along any direction with windmove-delete-*, for example. But we cover better ways to do this below.

Tiling manager integration

Tiling manager integration

If you use Emacs in a tiling environment, you’ve got a nested tiling window manager situation – it might be desirable to integrate the two so you can (wind)move seamlessly across Emacs windows and OS windows with the same keys. (Vim+tmux users should be familiar with this.) It takes a bit of work but is quite doable: Pavel Korytov has an i3 integration description for Emacs+i3wm (and possibly Sway), and I wrote one for the qtile window manager. I discuss this project in more detail below.

frames-only-mode

frames-only-mode offers: to leave Emacs window handling to the OS.

While we’re on the subject of tiling, another resolution to the nested window manager situation – Emacs inside a tiling WM – is to simply not bother with Emacs’ window management. Opening every buffer in a new frame instead of window makes corralling them the window manager’s job. This puts Emacs buffers on par with OS windows, and you can manage both with the same keys.

Most other commands described in this write-up (such as Avy, winum, ace-window or scroll-other-window) can work across frames just as easily as windows, meaning that you can have the best of both approaches. There are bound to be edge cases with other Emacs commands though – many of them make assumptions about being able to split the frame at will

This is especially true of org-mode commands! Thankfully the Org situation is slowly improving.

.

For Linux users:

I haven’t tried frames-only-mode with Wayland compositors yet.

winum-mode

winum offers: Selecting and deleting windows

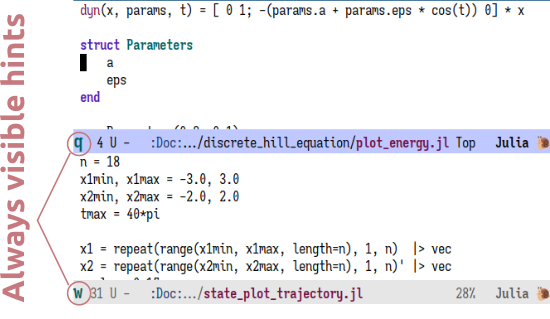

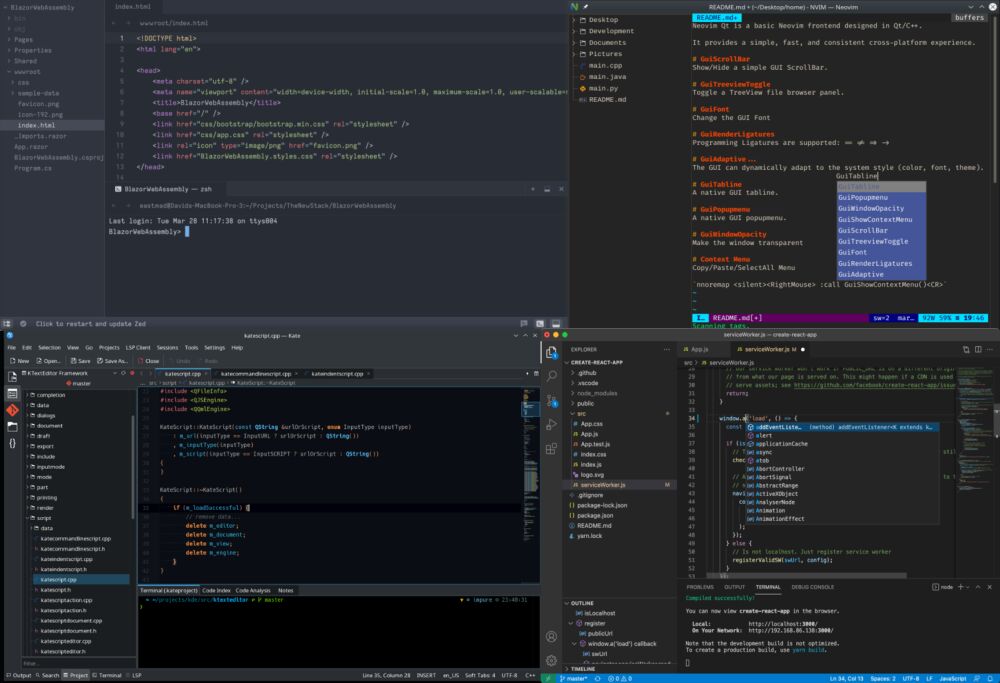

Winum is next in the natural progression of the effort to switch between n windows: From O(n) (other-window) to O(√n) (windmove) to O(1). It adds window numbers to the mode-line so you can select windows by number:

There are two convenient bonus features:

- Invoking the command to switch to a window with a negative prefix argument deletes the window, and

- when the minibuffer is active, it is always assigned the number 0.

It’s simple and short, and works across Emacs frames. winum-mode is the method I use the most for switching windows.

Speeding up window access with winum

Speeding up window access with winum

The default keybinding (C-x w <n> to select window n) is too verbose for my liking, as is any other two step keybinding. If you don’t mind losing access to digit arguments with M-0 through M-9, you can use them to select windows instead:

(defvar-keymap winum-keymap

:doc "Keymap for winum-mode actions."

"M-0" 'winum-select-window-0-or-10

"M-1" 'winum-select-window-1

"M-2" 'winum-select-window-2

"M-3" 'winum-select-window-3

"M-4" 'winum-select-window-4

"M-5" 'winum-select-window-5

"M-6" 'winum-select-window-6

"M-7" 'winum-select-window-7

"M-8" 'winum-select-window-8

"M-9" 'winum-select-window-9)

(require 'winum)

(winum-mode)

While it is possible to extend winum-mode to include other actions on windows (or on buffers displayed in them) besides switching to or deleting them, there’s little reason to, thanks to the existence of…

ace-window

Offers: Any window or buffer management action

ace-window is the endgame for keyboard-driven Emacs window control.

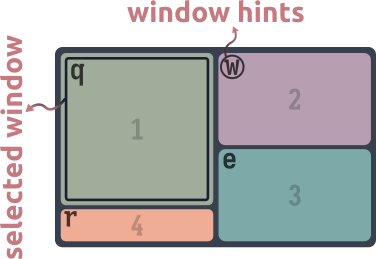

The ace-window command places “hints” at the top of each window, and typing in the key switches focus to the corresponding one:

So far it’s a slightly slower, two-stage version of winum. You can turn on ace-window-display-mode to have the hints always showing in the mode-line like winum’s window numbers, which speeds up the process a bit:

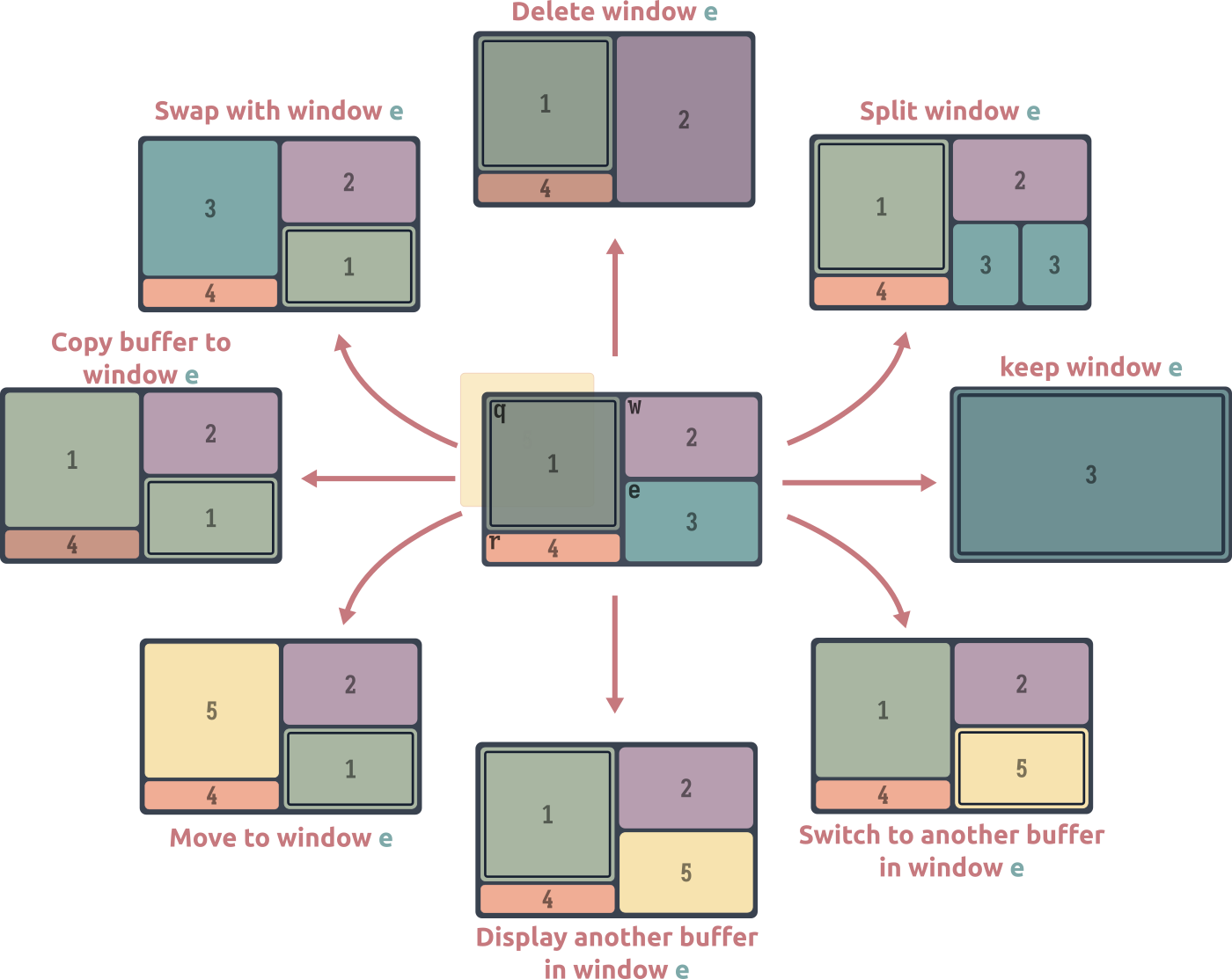

ace-window is to windows what Avy is to characters on screen The similar design is not a coincidence. They’re both authored by Oleh Krehel. . But jumping to a character on screen is the least useful of the many things you can do with Avy. Similarly, if all ace-window could do was switch windows, there wouldn’t be much to recommend it. Instead, it offers a generic method to “pick” a window, across all visible Emacs frames if necessary. What you do with this window is up to you. Similar to Avy, ace-window can dispatch actions on any window on the screen. So you can delete windows, move or swap them around, split them, show buffers in them and more – without moving away from your selected window. These are just the built-in actions, provided as part of ace-window:

Pressing ? when using ace-window brings up the dispatch menu

See Fifteen ways to use Embark for further explorations of this idea.

.

Play by play

- With two or more windows open, call

ace-window. (For two windows or fewer, you will need to ensure that the variableaw-dispatch-alwaysis set tot.) - Press

?to bring up the dispatch menu. - Press the dispatch key to split a window horizontally (

vin my video) - Press the ace-window key corresponding to the buffer you want to split (

ein my video) - Repeat steps 1 and 2

- Press the dispatch key to split a window vertically (

sin my video) - Press the ace-window key corresponding to the buffer you want to split (

win my video)

Mousing around (built-in)

The mouse offers: Any window or buffer management action

So, the pointer. Finally.

The advantanges of using the mouse for window management are immediate and obvious. Window selection is a natural extension of basic mouse usage. Resizing windows is a snap. Context (right-click) menus and drag and drop support, which improve with each new Emacs release, are very intuitive

See context-menu-mode. Also, while not limited to window management, discoverability via Emacs’ menu-bar is surprisingly good.

. Unfortunately, I have to address the rodent in the room before we can talk about mitigating the disadvantages, since Emacs users tend to be very opinionated about mouse usage.

I never use the mouse in Emacs… until I’m already using the mouse for something else. Then driving Emacs with the mouse is actually the path of least resistance. If your hand’s already off the keyboard, it’s pretty easy to drive Emacs with the mouse:

Play by play

This demo showcases the use of mouse gestures to do the following:

- Split the frame vertically and horizontally

- Delete windows

- Cycle through buffers in windows

- Swap windows to the right and left

- Toggle between the last two buffers shown in a window

You may want to turn on focus-follows-mouse behavior:

;; Consider setting this to a negative number

(setq mouse-autoselect-window t)

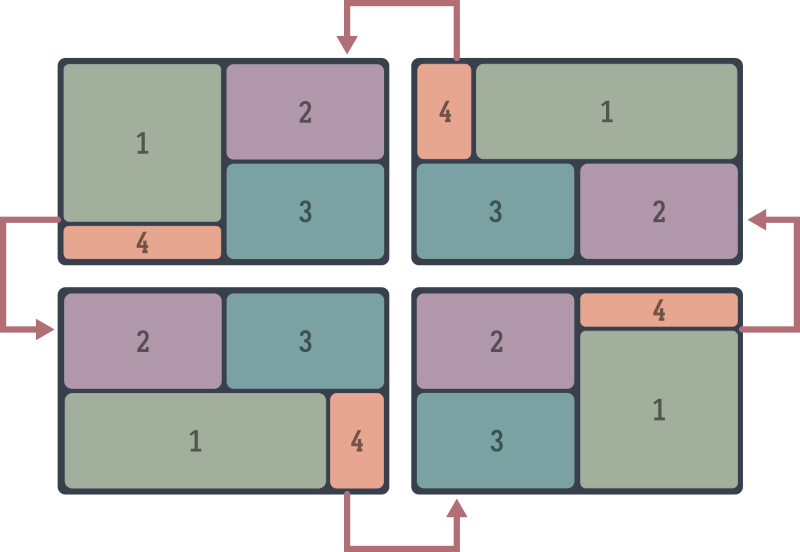

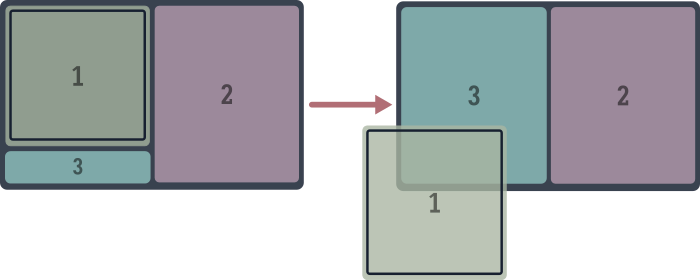

transpose-frame (rotation, flip and flop)

transpose-frame offers: easy window layout transformations.

What it says on the tin: transpose-frame offers commands to rotate or mirror the window layout on the frame. I found myself using these often enough to bind rotate-frame, flip-frame and flop-frame to suitable keys. Ironically, the transpose-frame command itself is rarely useful – it transposes along the main diagonal of the frame.

rotate-frame

flip-frame

flop-frame

The window-prefix-map (built-in)

window-prefix-map offers: Bespoke window management commands

The window-prefix-map, bound to C-x w by default in Emacs, collects a few useful window-management commands:

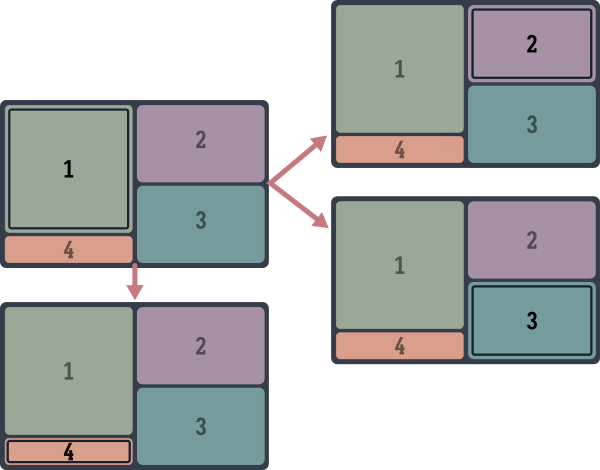

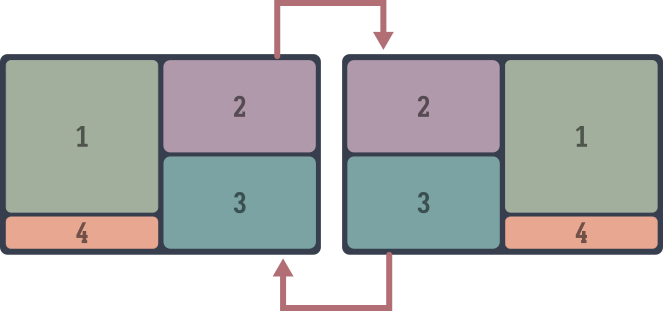

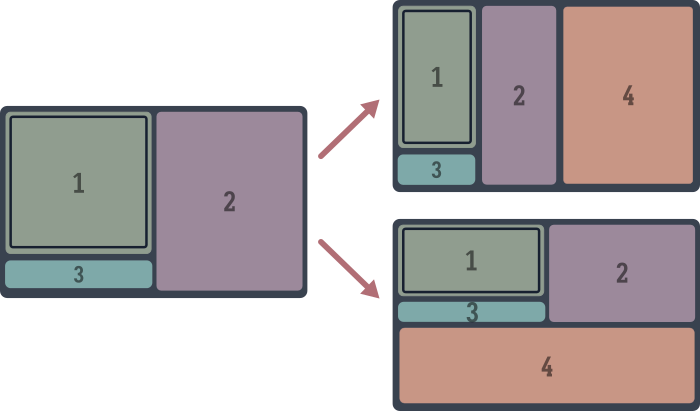

split-root-window-right and split-root-window-below

Split the root window of the frame. Better illustrated than explained:

These are bound to C-x w 3 and C-x w 2 respectively.

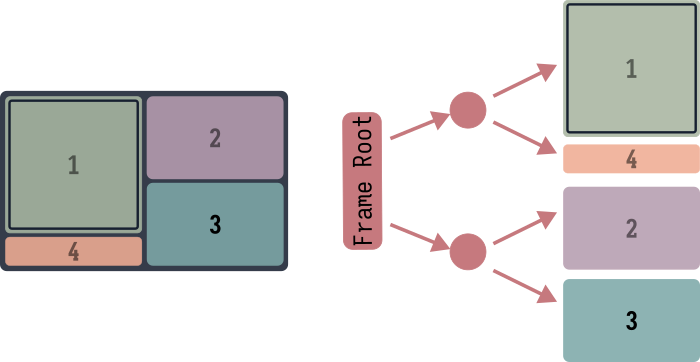

The window tree

The window tree

This is a good time to mention that windows in Emacs are arranged in a tree, with all “real” windows as leaves. Each splitting action turns a leaf node into a parent of two windows: the window that was split and the new one. This is very similar to the window arrangement in manual tiling window managers like i3 or bspwm, leading to a redundancy we seek to patch over.

These are the only built-in Emacs commands, to my knowledge, that allow you to modify the tree structure at a non-leaf level that doesn’t just clear the whole tree (as delete-other-windows does). Practically speaking, these are often useful to create a space for a logically separate task in the frame – the default splitting commands only further dice up existing windows.

Getting to grips with the tree arrangment should make a lot more fine-grained control available, but the tooling isn’t there yet – see below for a proposal.

tab-window-detach and tear-off-window

Handy commands to move a window into a new tab or a new frame.

Like splitting the root window, these are quite handy for logical window management: grab a window and move it into a new tab or frame to start a new task.

These are bound to C-x w ^ t and C-x w ^ f, which sheesh. You can do these as ace-window dispatch actions instead, since you can do anything with ace-window. Alternatively you can rebind these to the slightly saner C-x w t and C-x w f, which are currently unbound. I prefer to just use the mouse when I need to tear off a window:

;; mouse-9 is the "forward" button on my mousee

(keymap-global-set "M-<mouse-9>" 'tear-off-window)

The other-window-prefix (built-in)

other-window-prefix offers a method to decouple window selection from buffer display, and solves three window-related annoyances.

Annoyance I

Many Emacs commands tightly couple a primary action, a buffer and a window. For example, running find-file involves selecting a file, creating a buffer and displaying it in the current window. If you want to decouple the choice of window from the command, you have to pick one of several alternate commands: find-file-other-window, find-file-other-tab or find-file-other-frame, each with its own keybinding. If you want to open the file in read-only mode, you’ve got find-file-read-only, find-file-read-only-other-window, find-file-read-only-other-tab and find-file-read-only-other-frame. More keybindings.

Want the same choices when selecting a buffer? You’ve got switch-to-buffer-⋆, another constellation of commands. Opening a bookmark with bookmark-jump? Pick one of several bookmark-jump-* commands. This is the road to insanity.

The problem is the coupling: picking a window to display a buffer should be a separable action from the command’s primary function: opening a file, in this example. The solution is to call other-window-prefix, bound to (C-x 4 4). This makes it so that the next command – any command that involves displaying a buffer in a window – is shown in the next window, creating one if necessary. Now you only need find-file, find-file-read-only and switch-to-buffer, and can use the prefix to redirect the resulting buffer to another window when required:

- Call

other-window-prefix(C-x 4 4) - Call

find-file,find-file-read-only,switch-to-buffer,bookmark-jump, or any command that shows a buffer. - Result: the buffer is shown in the next window.

In a past write-up I’ve mentioned Embark as the way. Indeed, Embark solves this problem more elegantly than the built-in other-window-prefix. But avoiding command proliferation is only the first of three problems other-window-prefix solves.

Annoyance II

In the above examples, we at least have the choice of calling *command*-other-window instead of *command*. There are just too many options. More often there are none, and we’re at the mercy of fixed, undesirable behavior. This is typically the case when activating a link-like object. In this example (from the Forge package), pressing RET on an issue title opens the issue in the current buffer:

Play by play

This is a list of issues from a code repository, as displayed by the Forge package.

- Press

RETon an issue. - It opens in the current window, denying us the Listing & Item pattern: a simultaneous view of the full listing and the selected issue.

Forge provides no way, as of this writing, to “open a link” in another window. other-window-prefix to the rescue:

Play by play

- Call

other-window-prefix, viaC-x 4 4 - Press

RETon the issue. It opens in the “next window” – there isn’t one so a new window is created.

Annoyance III

The third problem it solves is the combination of the first two. Consider: Magit, the sibling package to Forge, does provide a way to do this. It generally opens “links” in the next window if you use a universal arg (C-u) before RET. Org mode, Notmuch, Elfeed and EWW all provide either no way or mutually distinct ways of opening links in a different window. If Forge did provide a way, it would actually make things worse in a sense. With other-window-prefix, you’re blessedly free from having to customize or conform to each package author’s idea of how this should work. Run other-window-prefix, then activate the “link” object – click on it with the mouse if you’d like. It’s going to uniformly open in the next window.

See also: same-window-prefix (C-x 4 1), which forces the next command’s buffer (if there is one) to use the current window, and other-frame-prefix (C-x 5 5) and other-tab-prefix (C-x t t), which open the next command’s buffer in a new frame and tab respectively.

What’s with these keybindings?

What’s with these keybindings?

There is a method to the seeming madness of keybindings like C-x 4 4, C-x 4 1 and C-x 5 5.

Keybindings involving specific window actions are grouped into prefixes, like a menu. C-x 4, the ctl-x-4-map broadly contains commands that use the other-window. For instance, C-x 4 . jumps to the definition of the thing at point (like the default M-.), but in the other-window. Most commands in the ctl-x-5-map create a new frame. Tab-bar actions are grouped under C-x t.

The final “base” key in each map follows a consistent pattern: f opens files, r opens things in read-only mode, b switches to buffers and so on. The final 4, 5 and t in C-x 4 4, C-x 5 5 and C-x t t reinforce the idea that the next buffer action is going to be redirected to another window, a new frame and tab respectively.

Further below we take this approach to its logical extreme with (what else) ace-window, redirecting the next command’s buffer to any window, including ones we create just-in-time.

Saving and restoring window configurations

window-configuration-to-register is a bit of a blunt instrument, but perfect as a big red reset button, especially if you’re new to Emacs. At any point, you can save the current window configuration to a register

A register is a named bucket that can hold many kinds of data. Each register is assigned to a character (like a through z), and operations on register are available under the C-x r prefix.

with this command, bound to C-x r w by default. After Emacs predictably messes up the frame, you can restore your saved configuration with jump-to-register (C-x r j). That’s it.

Persisting window configurations across restarts

Persisting window configurations across restarts

The elisp version of window-configuration-to-register is the function current-window-configuration, whose return value you can bind to a variable, and apply to the frame with set-window-configuration. Coupled with a way to persist this lisp object data to disk, such as with prin1 or via a library like persist or multisession, we have the seed of a state restoration feature that works across Emacs sessions. Needless to say, this approach is rudimentary and you’re better off using one of the many packages listed above in window configuration persistence.

One issue with this method is that it restores the window arrangement down to each window’s cursor position, which is rarely what you want.

Another problem is that it requires an unreasonable level of foresight to remember to save window configurations at appropriate times. If only Emacs could do this automatically for us every time the window configuration changed…

The “oops” options

…which of course it can. You can ask Emacs to maintain a stack of your past window arrangements, and cycle through them as you would through changes in a buffer with undo/redo. You’ve got three minor-modes depending on how you use Emacs, and you can turn them on independently.

winner-mode- If you don’t use tabs. Call

winner-undoandwinner-redoto undo/redo window configuration changes. It maintains a separate window configuration history for each frame. tab-bar-history-mode- If you use tabs. Each tab gets its own history stack. The relevant commands are

tab-bar-history-backandtab-bar-history-forward. undelete-frame-modeandtab-undo- If you use create and delete frames or tabs all the time. If you close a frame by accident, you can call

undelete-frame, bound toC-x 5 u. Dittotab-undo, bound toC-x t u.

These options are handy for going on excursions, such as when you want to maximize the selected window temporarily before reverting to the previous arrangement.

But winner-mode & co are also frequently recommended as a band-aid for when Emacs messes up your careful manual window arrangement, for instance by popping up windows in the wrong places, or resizing your window splits. I think of this as an antipattern. If you find yourself using winner-undo (or equivalent) all the time to fix Emacs’ behavior, the problem is Emacs displaying buffers in the wrong windows in the first place, a result of frustrating defaults. See the whack-a-mole problem.

Digging in

With our appetite whetted, we can move onto our main course: Tweaks, customization and variations of the above tools that I’ve found to work better.

Emacs can be frustrating on two levels. It’s frustrating at first because you don’t know your way around the place, the keybindings and terminology are obtuse, and nothing works the way it does in other software. Your attempts at mitigating its perceived shortcomings by installing packages leads to mysterious, cryptic errors. The single-threadedness makes it too easy to accidentally slow things down to a crawl. The garbage collector fires at the worst times. Things that should just work, don’t. The perceived shortcomings of Emacs are frustrating: Window management shouldn’t be this complicated!

Over time (years, decades?) you can develop a better mental model of what’s happening under the hood: how Emacs’ event loop works, the anatomy of buffers, windows, keymaps, text properties and overlays – the data structures Emacs is built on. Perhaps you even steal some sneaking glances at the lumbering behemoth that is redisplay. You’re familiar with common Elisp idioms and macros, as well as the common traps. Now the actual shortcomings of Emacs’ API are frustrating: Window management shouldn’t be this complicated!

Oops.

So here we are. The rest of this write-up is aimed at someone in between these two kinds of frustration. It’s mostly me throwing out suggestions, many of them mutually exclusive, that might give you ideas of your own to work with windows. Implementing these ideas will require a little tweaking, copying code verbatim might not give you the results you expect. For this reason, I suggest coming back here with a little more Emacs mileage if you’re new to Emacs.

The back-and-forth method

Offers: Quick window selection

An observation: no matter how many simultaneous windows you have or require on screen, most of the time you only need to switch between two of them. Examples include the Code & REPL setup, the Code & Grep (search results) setup, and the Prose & Notes setup. The Listing & Item pattern is an example outside of programming or prose: this includes a calendar or agenda window with an expanded entry window, or an email inbox window with an opened email.

The other windows on screen usually show useful information – documentation, debugging info, messages, logs or command output, table of contents, a file explorer, document previews – things you glance at often but switch to rarely.

Usually major-modes provide semi-consistent keybindings to switch back and forth between two associated windows – a common example is C-c C-z, used by several programming modes in Emacs to switch between a code window and an associated REPL

This works for Org-babel blocks too via org-babel-switch-to-session, bound via org-babel-map to the slightly different C-c C-v C-z.

.

But we can generalize the idea and provide a command to switch between any pair of windows:

(defun other-window-mru ()

"Select the most recently used window on this frame."

(interactive)

(when-let ((mru-window

(get-mru-window

nil nil 'not-this-one-dummy)))

(select-window mru-window)))

(keymap-global-set "M-o" 'other-window-mru)

It doesn’t matter how you select the second window for the back-and-forth – you could use the mouse, ace-window, winum or any other method. other-window-mru’s got you covered from then on.

Improving other-window

We can retain the basic idea of other-window – move between windows in the frame in some cyclic ordering – but improve the ordering to be more of a DWIM affair

Do-What-I-Mean

.

other-window is a simple idea – the simplest you’ll find in this write-up – but you can play around with the order in which windows are selected to better fit how you work.

Double duty

First, you could make other-window split the frame when there’s only one window, giving the command a use when it has none.

(advice-add 'other-window :before

(defun other-window-split-if-single (&rest _)

"Split the frame if there is a single window."

(when (one-window-p) (split-window-sensibly))))

switchy-window

Another modification that you might find intuitive is to cycle through windows in order of last use instead of in clockwise spatial order, similar to alt-tab or how some web browsers cycle through tabs. This is possible with some elbow grease, but this work has been done for us by the switchy-window package, which provides a switchy-window substitute command for other-window.

When cycling through windows, switchy-window waits for a window to stay selected for a couple of seconds before marking it as used and updating the recency list. In practice this works quite seamlessly – calling switchy-window moves you to to where you need to be most of the time.

That said, I usually prefer the simpler variant described in the back-and-forth method.

other-window-alternating

And speaking of back-and-forth, here’s another other-window variant – it might sound confusing at first, but turns out to be a pleasingly DWIM affair. Except when chaining other-window, reverse the window-switching direction after each call. With just two windows, this makes no difference. With more, this makes alternating between two windows natural, even when the windows are not adjacent in the cyclic ordering.

(defalias 'other-window-alternating

(let ((direction 1))

(lambda (&optional arg)

"Call `other-window', switching directions each time."

(interactive)

(if (equal last-command 'other-window-alternating)

(other-window (* direction (or arg 1)))

(setq direction (- direction))

(other-window (* direction (or arg 1)))))))

(keymap-global-set "M-o" 'other-window-alternating)

;; repeat-mode integration

(put 'other-window-alternating 'repeat-map 'other-window-repeat-map)

(keymap-set other-window-repeat-map "o" 'other-window-alternating)

Window magic with ace-window dispatch

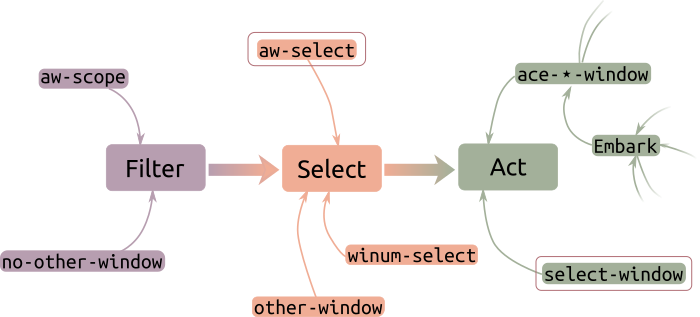

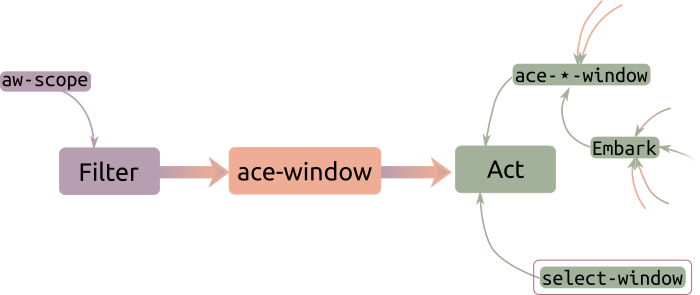

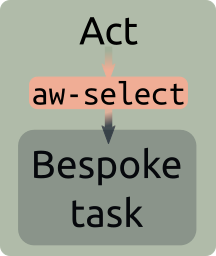

ace-window is to windows what completing-read is to lists of strings, or Avy to characters on screen. This makes it ideal as the first two of a three-step process to invoke any action on any window: the filter and selection steps:

aw-select, the completing-read for Emacs windows

The way ace-window is designed to be extended is by defining an “ace-window action” and adding a binding for it in aw-dispatch-alist

It ships with several predefined actions, captured in this schematic above.

. This function accepts a window and does something useful with it. The ace-window command acts as the entry point:

This control flow is generally similar to how Avy works. But as a completing-read alternative, this is somewhat lacking – we’d like to flip the pattern around and use ace-window’s selection method in our commands. Conveniently, aw-select does exactly that.

The basic pattern is very simple: the call (aw-select nil)

The argument to aw-select is for adding a message to the mode-line during the selection process, we don’t bother with that.

returns the window we select, which we can use for our task. One example of such a task is to set the window that scroll-other-window should scroll. Here are a couple more, but don’t try them just yet! We’re going to generalize the idea a little further below.

tear-off-window or tab-window-detach

Every interactive window command in Emacs acts on the current window. Here we make a couple of commands in the window-prefix-map (C-x w) something you can apply interactively to any window.

(defun ace-tear-off-window ()

"Select a window with ace-window and tear it off the frame.

This displays the window in a new frame, see `tear-off-window'."

(interactive)

(when-let ((win (aw-select " ACE"))

(buf (window-buffer win))

(frame (make-frame)))

(select-frame frame)

(pop-to-buffer-same-window buf)

(delete-window win)))

(defun ace-tab-window-detach ()

"Select a window with ace-window and move it to a new tab."

(interactive)

(when-let ((win (aw-select " ACE")))

(with-selected-window win

(tab-window-detach))))

Of course, defining one ace-window-based command for each action isn’t a scalable or useful way to go about this. It would be preferable to decouple the window selection step from the action step and generalize the latter. We explore two distinct approaches to do this, starting with…

ace-window-one-command: Any command with ace-window

Generalizing the above examples gives us a pretty good idea of what the flipped ace-window pattern should look like. The most general and composable version would be the following:

- Call

aw-selectto pick a window (thecompleting-readstep) - Run any action in this window

- Switch back to the original window.

We can do this by simulating Emacs’ event loop, but in the chosen window: Switch windows, then read any key sequence and execute it before switching back.

(defun ace-window-one-command ()

(interactive)

(let ((win (aw-select " ACE")))

(when (windowp win)

(with-selected-window win

(let* ((command (key-binding

(read-key-sequence

(format "Run in %s..." (buffer-name)))))

(this-command command))

(call-interactively command))))))

(keymap-global-set "C-x O" 'ace-window-one-command)

In a demo, this looks the same as ace-window, except that you select the window before executing the action. The win here is the action: it works with any simple command, there is no need to pre-configure actions in aw-dispatch-alist. There’s nothing to set up or memorize. In this demo I use ace-window-run-command to shrink an unselected window with C-x - (the descriptively named shrink-window-if-larger-than-buffer)

Play by play

- Pulse the line to show which window is active.

- Call

ace-window-one-actionand select the Occur buffer to the top left. Emacs waits for you to execute any single command. - Run

shrink-window-if-larger-than-buffer, usingC-x -. This shrinks the Occur buffer, our cursor position and window is unchanged.

ace-window-one-command is a convenient way to quickly run any command in a different window, an idea we explore in more detail below.

Embark much?

Embark much?

This reversal of Emacs’ (and ace-window’s) usual paradigm of action → selection is at the heart of Embark, as covered in my write-up on ways to use Embark. Of course, this “object-first” approach is only one way to look at it – Embark has many hearts.

A window-prefix command for ace-window

Handy as it is, the other-window-prefix system has the same problem as the other-window command: it enforces a rigid cyclic ordering on the window it will pick, and about the most we can consistently expect is that the active window will not be taken over by the next command. We can do better.

aw-select gives us a bespoke solution with more control: we select the window that should be used if the next command involves displaying a buffer in a window. In this example, we explicitly pick a window to show a man page in, since the “next window” is not where we want it:

Play by play

- Pulse the line to indicate the active window (lower left)

- Run

ace-window-dispatch(C-x 4 o), thenM-x manand choosecurl(1). Emacs waits for us to pick a window. - Pick the window on the right with “e”. The Man page is displayed in that window.

Note that the Man elisp library actually offers a suite of options to customize where it should be displayed, in the fiddly way typical of all things Emacs. We can sidestep that whole undertaking here.

Here’s the example from above of viewing a Forge link in a busy frame with many windows. We compare the result of using other-window-prefix, where a random window is chosen, to using ace-window-prefix, where we can pick a specific window:

Play by play

In this frame, the window “next” to the Forge topics window (the bottome one) is the one window at the top left.

- Move down to the last listed topic and pulse the line (so you can find the active window)

- Call

other-window-prefix(C-x 4 4) and pressRETon the “link”. It opens in the top left window, not where we’d like to see it. - Call

tab-bar-history-backto restore the previous window configuration. - Call

ace-window-prefix(C-x 4 o) instead, and pressRET. Emacs waits for us to pick a window to show the resulting buffer in. - Pick the window on the right with “r”. Forge shows the link contents in that window.

ace-window works across visible frames, so we can pick any Emacs window on our screen. Even better, we can use ace-window actions to create new windows on the fly and use them instead. Here I use an ace-window action to create a new window to be used by the next command:

Play by play

Normally, activating an Org mode link opens it in the current window or the next one, depending on your Org settings. We want something different.

- Press

RETon the link to open the image in the next window. - Press

qto quit and return to the Org buffer. - Call

ace-window-prefixand pressRETon the link. Emacs waits for us to pick a window to show the linked file in. - Use an

ace-windowaction to split a window and select the split. The action now finishes and the linked image is shown in that window.

The implementation of ace-window-prefix is actually simpler than other-window-prefix:

(defun ace-window-prefix ()

"Use `ace-window' to display the buffer of the next command.

The next buffer is the buffer displayed by the next command invoked

immediately after this command (ignoring reading from the minibuffer).

Creates a new window before displaying the buffer.

When `switch-to-buffer-obey-display-actions' is non-nil,

`switch-to-buffer' commands are also supported."

(interactive)

(display-buffer-override-next-command

(lambda (buffer _)

(let (window type)

(setq

window (aw-select (propertize " ACE" 'face 'mode-line-highlight))

type 'reuse)

(cons window type)))

nil "[ace-window]")

(message "Use `ace-window' to display next command buffer..."))

In keeping with the keybinding pattern for the ⋆-window-prefix commands, we bind it to C-x 4 o

(keymap-global-set "C-x 4 o" 'ace-window-prefix)

Do you need to switch windows?

Let’s pause for a moment to ask a basic question: why do you need to switch windows in the first place? A little reductive thinking distills the answer down to two – and only two – possibilities:

- Switch and stay: To work persistently in the destination window, for some measure of “work”: this covers text editing in all its forms. In this event the window we switch to becomes our primary work area.

- Switch and return: To interact with the window or its contents briefly. Perhaps we want to scroll through, or copy some text before moving back, or to delete the window. In this event the window is a temporary destination, for auxiliary purposes.

In either case, switching windows is a cost, not our objective. Ideally this should happen automatically as part of our editing process. So why not just “fold” this little chore into our primary editing action?

Switch and stay: Avy as a window switcher

Eventually any kind of navigation in Emacs comes down to Avy. If you are switching windows to edit (or select) text, you intend to move to a specific point on the screen. Getting the cursor there is a two step process: switch windows, move the cursor to the right location. Avy short-circuits this process into a single action. It treats the frame as a single pool of jump locations: in helping you jump to any character(s) on the screen, it moves you across windows seamlessly:

Play by play

- Call

avy-goto-char-timer - Type in “se”. This shows hints for all matches with “se”, including “sentence”.

- Type in the hint char corresponding to “sentence”, which is

ghere.

With a slight mental shift you can stop thinking of windows as distinct objects entirely, at least for the purposes of navigation. Any character(s) – across all visible Emacs windows and frames – is a couple of keypresses away. And it’s not the only way to jump across windows: you can jump back to your starting point (switching windows in the process) with pop-global-mark, for instance:

Play by play

- Call

avy-goto-char-timer - Type in “demo”. There is only one candidate for this string, so Avy jumps to the other window.

- Type in “jump”. This shows hints for all matches with “jump”.

- Pick one of the matches. Avy jumps again, this time to the third window.

- Call

pop-global-mark(C-x C-SPC) to jump back to the previous location. (Details below) - Call

pop-global-mark(C-x C-SPC) again to jump back to the previous location.

Making Avy window-agnostic

Making Avy window-agnostic

If Avy does not move you across windows and frames, you probably need to customize avy-all-windows.

While we’re here, consider customizing avy-style, there’s more than one way to jump with Avy!

Of course, this only scratches the surface of what you can do with Avy, but that’s well tread ground at this point.

Switch and return: Actions in other windows

And here’s the other case. Often the reason you switch windows is to run a single logical action – perhaps a compound action like isearching to focus the view somewhere, before switching back to your main buffer. This is the switch → act → switch-back dance.

We’re going to automate this dance away in steps, working through solutions obvious and specific, through to repeatable and general, ending at the abstract and generic.

The obvious first: if you find yourself performing this dance repeatedly, you can automate it with a keyboard macro (left as an exercise for the reader). If the action is something you do all the time, you can go a step further and write a general-purpose command. ace-window-one-command above would be one way to do it. Emacs paves the way for us with…

scroll-other-window (built-in)

scroll-other-window and scroll-other-window-down have been part of Emacs for ages, perhaps because it fits neatly into the two-window paradigm that Emacs’ default settings are suited for: editing in one window while using the contents of the other one as a reference. You can scroll up and down in the other window without leaving this one. Note that this works with any number of windows: the window that is scrolled is the “next window”, clockwise from the current one. In this schematic, the selected window is the one with the border, the one that scroll-other-window scrolls is the one with the arrows:

With more than two windows this requires careful placement of windows to work as expected. For instance, you cannot have three side-by-side buffers (1-3 above) and use 1 as a reference when working in both 2 and 3, since scroll-other-window in 2 will scroll 3. Thankfully, we can specify the rule by which to select the window for scrolling. One option is

(setq other-window-scroll-default #'get-lru-window)

which will always scroll the least-recently-used window, since you won’t be wading into buffer 1 – the reference – often. Alternatively, you might want scroll-other-window in buffers 2 and 3 to scroll each other as you switch between them and ignore buffer 1. You’d then use the most-recently-used window:

(setq other-window-scroll-default

(lambda ()

(or (get-mru-window nil nil 'not-this-one-dummy)

(next-window) ;fall back to next window

(next-window nil nil 'visible))))

This works great with The back-and-forth method.

Setting the window to scroll

Setting the window to scroll

There is another way to change the window that is scrolled instead: by setting a variable (other-window-scroll-buffer), you can specify the buffer whose window should be scrolled instead of the next window. But this is mostly an option for package authors. To do it on the fly, we’d need to write another elisp command, something like

(defun ace-set-other-window ()

"Select a window with ace-window and set it as the \"other

window\" for the current one."

(when-let* ((win (aw-select " ACE"))

(buf (window-buffer buf)))

(setq-local other-window-scroll-buffer buf)))

This is only useful if we want this association to be persistent. Otherwise the LRU/MRU method does what we need most of the time. See also master-mode below.

Scrolling other windows: minutiae

Scrolling other windows: minutiae

-

The viability of the default bindings for

scroll-other-window(C-M-vandC-M-S-v) depends on your tolerance for modifiers. A good candidate for remapping, especially if you use a modal input method.C-M-vcan be invoked asESC C-valready, I bind the other one toESC M-v. -

scroll-other-windowworks from the minibuffer too. The window scrolled is usually the one that the minibuffer-using command was invoked from, and can be set explicitly as the value ofminibuffer-scroll-window. -

From Emacs 29 onwards,

scroll-other-windowis better at handling non-text buffers like PDFs, where scrolling is handled by special functions. It now calls whatever the standard scrolling commands (scroll-up-commandandscroll-down-command) are bound to. To scroll PDF buffers managed by the pdf-tools package in the “next window” position, for instance:(with-eval-after-load 'pdf-tools (keymap-set pdf-view-mode-map "<remap> <scroll-up-command>" #'pdf-view-scroll-up-or-next-page) (keymap-set pdf-view-mode-map "<remap> <scroll-down-command>" #'pdf-view-scroll-down-or-previous-page))Another example: after rebinding the regular paging commands via

pixel-scroll-precision-mode,scroll-other-windowwill smooth-scroll the other window:

isearch-other-window

Continuing with the idea of using a buffer in another window as a reference, a straightforward extension of scroll-other-window is to search the “next window” instead

isearch is a fantastic navigational tool.

. We make sure to search in the same window that we’ve configured to scroll with scroll-other-window above.

(defun isearch-other-window (regexp-p)

"Function to isearch-forward in the next window.

With prefix arg REGEXP-P, perform a regular expression search."

(interactive "P")

(unless (one-window-p)

(with-selected-window (other-window-for-scrolling)

(isearch-forward regexp-p))))

(keymap-global-set "C-M-s" #'isearch-other-window)

The function other-window-for-scrolling returns a suitable window, respecting our choice of other-window-scroll-default above.

Here’s an example of using isearch-other-window to work in a shell and a documentation (Man) buffer together:

Play by play

- Type in a partial Curl command

- Invoke

isearch-other-window(C-M-shere), which starts searching the Man buffer - Search for

--ssl revoke, which finds the option we’re looking for. (This special matching behavior is from settingisearch-whitespace-regexp.) - Pressing

RETends isearch and we’re back in the shell. - Scroll the other window with

scroll-other-window, then usehippie-expandto type in the argument we want.

The keybinding C-M-s is already bound to isearch-forward-regexp, but there are many other ways to call that command: via a prefix arg to isearch-forward (C-u C-s), or by toggling regexp search with M-r when isearching, for instance.

Performing actions in other windows

Performing actions in other windows

There are two simple ways to temporarily switch to another window in elisp: (save-window-excursion (select-window somewin) ...) and (with-selected-window somewin ...).

For our purposes, the difference between them is that the former restores the window configuration at the time it was executed, which includes the buffer positions relative to the windows and the values of (point) in the buffer. The latter persists changes across the frame, and is typically what we want. If the changes were not persistent, there would be no point to this exercise!

Switch buffers in the next window.

You can have hundreds of buffers in Emacs but only a handful of windows. This is, in fact, the source of the window management problem. So any comprehensive solution has to involve changing buffers shown in existing windows. The ace-window dispatch system is one solution. But the built-in next-buffer and previous-buffer commands offer another easy 80% solution to changing buffers shown in other windows: we just automate away the window switching dance. We don’t need a dedicated next-buffer-other-window command for this – we can just replace next-buffer with the new function.

(defun my/next-buffer (&optional arg)

"Switch to the next ARGth buffer.

With a universal prefix arg, run in the next window."

(interactive "P")

(if-let (((equal arg '(4)))

(win (other-window-for-scrolling)))

(with-selected-window win

(next-buffer)

(setq prefix-arg current-prefix-arg))

(next-buffer arg)))

(defun my/previous-buffer (&optional arg)

"Switch to the previous ARGth buffer.

With a universal prefix arg, run in the next window."

(interactive "P")

(if-let (((equal arg '(4)))

(win (other-window-for-scrolling)))

(with-selected-window win

(previous-buffer)

(setq prefix-arg current-prefix-arg))

(previous-buffer arg)))

And we can take over next-buffer and previous-buffer:

(keymap-global-set "<remap> <next-buffer>" 'my/next-buffer)

(keymap-global-set "<remap> <previous-buffer>" 'my/previous-buffer)

Finally, we define a fallback version of switch-to-buffer and shove all of these into a repeat-map so we can call them consecutively with n, p and b:

;; switch-to-buffer, but possibly in the next window

(defun my/switch-buffer (&optional arg)

(interactive "P")

(run-at-time

0 nil

(lambda (&optional arg)

(if-let (((equal arg '(4)))

(win (other-window-for-scrolling)))

(with-selected-window win

(switch-to-buffer

(read-buffer-to-switch

(format "Switch to buffer (%S)" win))))

(call-interactively #'switch-to-buffer)))

arg))

(defvar-keymap buffer-cycle-map

:doc "Keymap for cycling through buffers, intended for `repeat-mode'."

:repeat t

"n" 'my/next-buffer

"p" 'my/previous-buffer

"b" 'my/switch-buffer)

The result of this keymap gymnastics, with key descriptions in the top right:

Play by play

- Call

my/next-bufferormy/previous-buffer(I’ve bound them toC-x C-nandC-x C-pinstead of remapping the defaultnext-bufferbindingC-x <right>). - This activates the repeat-map

buffer-cycle-map, so I can continue cycling through buffers withnandp. - Exit the repeat-map by pressing any other key.

- Call

my/next-bufferwith a prefix argument (C-u C-x C-n). This activates thebuffer-cycle-map, but in the other window, so you can cycle buffers in the other window withnandp. - Pressing

bwhen the repeat map is active callsswitch-to-bufferin the window that is selected. This is a fallback when the buffer you need is not one or two away in the window’s buffer history.

Using b to display a buffer in another window is consistent with how ace-window’s dispatch version works.

master-mode and scroll-all-mode

A passing note: Emacs provides master-mode, a bespoke solution for performing actions in other windows without leaving this one. You can designate a buffer as the “slave” buffer of the current buffer (the “master”). This opens up a keymap for scrolling the slave buffer without leaving the current one. By itself, this is a worse alternative to the more transparent and immediate solutions involving other-window-scroll-default above. But you can add to this keymap with the plumbing command master-says, which helps you set up keys to do predefined actions in the slave buffer. This built-in action, for example, recenters the slave buffer:

(defun master-says-recenter (&optional arg)

"Recenter the slave buffer.

See `recenter'."

(interactive)

(master-says 'recenter arg))

But this can be any action: you could set a shell or compilation buffer as the slave buffer of every project buffer, and use master-mode to page through them, copy the latest output, send commands and so on.

And while we’re focused on scrolling, scroll-all-mode is a simple way of tying together scroll actions in all windows on the frame. On occasions where you want to keep two more more window views in sync, this is a handier method than scrolling the active window and then the other window.

with-other-window: An elisp helper

What’s better than writing a general-purpose command to automate one switch → act → switch-back dance? A general-purpose macro to automate writing the general-purpose command! We can decouple the action from the switching with a macro:

(defmacro with-other-window (&rest body)

"Execute forms in BODY in the other-window."

`(unless (one-window-p)

(with-selected-window (other-window-for-scrolling)

,@body)))

The above examples become straightforward applications of this macro

(defun isearch-other-window (regexp-p)

(interactive "P")

(with-other-window (isearch-forward regexp-p)))

(defun isearch-other-window-backwards (regexp-p)

(interactive "P")

(with-other-window (isearch-backward regexp-p)))

This is the elisp counterpart to the interactive ace-window-one-command.

Do you need many windows?

The world seems to have converged on a single UI for editors: one main window, a tab bar at the top (with one window per tab), a directory or contents sidebar on the left, an optional doodad on the right, and a terminal emulator below.

Every editor got the memo… except Emacs, it appears. You could recreate this window layout and workflow in Emacs. Or any other, for that matter. But all this furious window management behooves us to ask an even more basic question: Why even have more than one window?

There’s some merit to this: the screen could be devoted to one buffer at a time, with buffer-switching taking the place of window switching. There’s no need to worry about resizing windows, and anything that pops up in the course of introspection or regular editing (like documentation windows) can be dismissed with a keypress, typically q. Special buffers like the file browser are accessible via dedicated commands like dired-jump.

Relaxing this requirement to two-windows-at-a-time helps retain most of the hassle-free behavior while adding the benefits of using the second window as a live reference. By default, Emacs is set up to do this well, as evidenced by scroll-other-window and other commands. No rigid layout imposed via decree from on high, but no chaotic structureless and windows popping up like weeds either.

Effectively, we’ve circled our way back to The Zen of Buffer Display. While it would be ironic if the window management freedom Emacs provides causes us to reject it, we can route around the problem and not deal with windows at all, irrespective of how many we’d like to have on screen simultaneously.

So here are two more strategies for window management, both of which involve minimizing dealing with windows. The first one is “window management” in the loosest sense of the term:

Windows are made up, let’s ignore them

Window-agnostic jumping with Avy is a special case of a general idea: when using Emacs, we are primarily concerned with text. As a container for text, a window can be an unnecessary abstraction. This framing is natural when a destination is outside the screen contents, such as when jumping to definitions with xref-find-definitions.

But there are several other ways to apply this window-agnosticism. The mark-ring and global-mark-ring keep track of locations we jump from, letting us jump back with pop-to-mark-command (C-u C-SPC) and pop-global-mark (C-x C-SPC), the latter of which can jump across windows if necessary. A package like dogears can provide more granular control and a nicer UI to retrace your steps.

Making

Making pop-to-buffer jump across windows.

By default, pop-global-mark always switches buffers (if required) in the current window. We’d like it to double as a window-switcher, which requires a little advice:

(define-advice pop-global-mark (:around (pgm) use-display-buffer)

"Make `pop-to-buffer' jump buffers via `display-buffer'."

(cl-letf (((symbol-function 'switch-to-buffer)

#'pop-to-buffer))

(funcall pgm)))

To manually pin a position to jump back to later, there is point-to-register (C-x r SPC) and jump-to-register (C-x r j). Again, this switches windows as a side-effect.

For more permanent records, you can create and jump to bookmarks with bookmark-set (C-x r m) and bookmark-jump (C-x r b).

Between these, you have plenty of options for navigating across windows to locations that are meaningful, as ascertained by either Emacs or you. These work just as well with a single window in an Emacs frame as they do with the canonical twenty-first century IDE window layout.

Deal with windows so we don’t have to deal with windows

i.e. Fixing the Whack-A-Mole window problem.

As much as this write-up is about manual actions involving Emacs windows, it was unavoidable: at some point I was going to have to mention display-buffer-alist and automatic window behavior. The idea is simple. Every time elisp code wants to show you a buffer, it tries to match the buffer it is displaying against a list of rules in this variable. The matching entry specifies how it should be displayed.

If we set up rules – specifying window sizes, positions, roles, focus – for every kind of buffer we see in our daily Emacs use, that’s most window management sorted… right?

Right, actually. The reality hews close to the aspiration. The problem with display-buffer-alist is not that it doesn’t work, but that it’s a lot of work. Creating rules for displaying buffers involves understanding many more aspects of Emacs’ API than is reasonable for most users: buffer and mode predicates, window types and slots, display-buffer action functions, window parameters, and a whole lot more gibberish. And at the end of this expedition into the elisp manual, there is no easy way to express a simple intention, like “do not disturb my window arrangement”

Specifying overreaching and overriding display-buffer preferences can do this, but they lead to dozens of edge cases and unintended behavior.

. As such, it’s a tool primarily used by package authors to surface a more approachable interface to specifying automatic window behaviors for their package.

But in the spirit of the almanac, let’s not leave this topic empty handed.

-

The Shackle package papers over the

display-buffer-alistoddness and presents a simplified elisp interface for specifying window rules. If you want to corral a couple of pesky buffer types that always ruin your window arrangement and have you reaching forwinner-undo, this is your best bet. -

Emacs distributions usually provide a simple interface for specifying these preferences. Doom Emacs provides a convenient

set-popup-rule!command for this. If you’re using one, you’re probably covered. -

And if you’ve got a hankering for tinkering, Mickey Peterson’s article on demystifying the window manager, this video by Protesilaos Stavrou and the elisp manual are all fine resources, as alluded to in the preface.

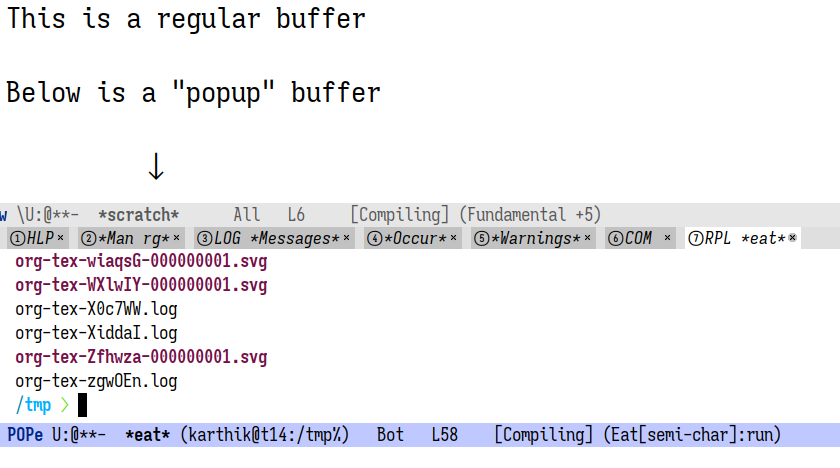

Popper, Popwin, shell-pop and vterm-toggle

While we’re aiming at the ideal of the minimal workspace uncluttered by windows, a popup manager is another helpful tool.

Popwin and Popper are Emacs packages based on the observation that not all buffers are created equal. There are (primary) buffers we spend most of our time in, and (popup) buffers we’d like to access temporarily – to use as a reference, page through documentation, run shell commands, check a task or compilation status, access search results, read messages, and so on. Using display-buffer-alist or an equivalent method, you can make these buffers use smaller, auxiliary windows and not grab the cursor when they appear. But that doesn’t solve the access problem: what we’d like is one key access to summon these popup buffers, and easy ways to dismiss their windows, cycle through or kill them.

Popper provides this for all kinds of buffers you choose to (pre-)designate as popups, helping you stick to the one (or two) window paradigm, raising and dismissing these auxiliary windows as needed. This image shows popups available in the current context as a line of tabs that can be accessed or cycled through with one key:

Popwin is an older and more comprehensive implementation of this idea, but it bundles together quick key access and its own bespoke display-buffer configuration, which may not be what you want. If you only want one key-access to summon and dismiss shell buffers, shell-pop or vterm-toggle might be all you need instead.

The Missing Pieces

We conclude with window management options that should exist… but don’t.

window-tree

There is a fundamental disconnect between how Emacs represents windows and how we manipulate them using the approaches discussed above.

Windows in a frame in Emacs are arranged in a tree: the leaf nodes are “live” (real) windows, and the rest are “internal” (virtual) windows

The minibuffer is technically not part of this tree, although it can be reached by traversing it. (See the window-tree function.)

.

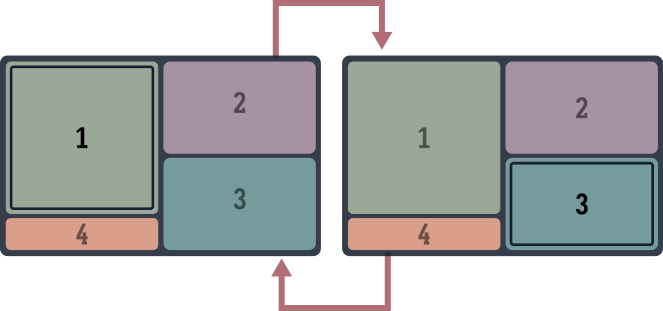

Most user-facing operations on windows, such as moving between them with other-window or Windmove, ignore the tree structure and work by examining their spatial positions instead. This often causes unexpected and unintuitive behavior when splitting or deleting windows, or imposes confusing constraints on what splits you can create. For example, there is no way to perform these transformations:

The window that needs to be split here is neither the frame root nor a leaf window – it’s some internal node in the tree.

Adding commands for window-tree operations opens the door to many new possibilities. Frame transformations like splitting, transposing, mirroring and so on are elementary operations on window-tree branches. Multiple window selection is possible via “selecting” internal windows, and partial window configurations can then be operated on, handed off to other tabs or frames, duplicated or persisted. Tree branches can be protected from being mangled by display-buffer and friends

This kind of all-or-nothing window behavior is currently enabled via Elisp’s atomic windows API, which is a significantly more restrictive approach.

, and you can have sections of a frame devoted to one task, with the sibling branch tolerating flexible, looser behavior.

How do we write this hypothetical wintree package?

- Elisp already provides functions to query the window tree:

window-treereturns the tree itself.frame-root-windowreturns the tree root, andwindow-parent,window-child,window-*-siblingdo what you’d expect. - There is some support for tree traversal via

walk-window-treeandwalk-windows. - There are no elementary functions for mutating the tree, except via splitting and deleting live windows the usual way.

- There is no concept of “selecting” an internal window, so this will have to be simulated via the UI, perhaps by adding a border inside each window in the sub-tree.

So some of the required elements are present. The missing ingredient is a motivated Emacs user (perhaps you) stepping into window.el and getting their hands dirty!

The tiling-wm integrator

Emacs’ window-tree model is almost exactly that of manual tiling window managers like i3 or bspwm, sans some affordances like i3’s tabbed windows. This leads us to a natural question: why use a tiling window manager inside of another one? Yo dawg, I heard you like tiling… If you use i3, bspwm or Emacs inside tmux, it’s natural to want to be able to navigate both seamlessly, with the same keybindings. There are a couple of Emacs packages for this: Pavel Korytov’s i3-integration, and something I hacked up for qtile. But providing a cleaner and more unified interface for this from Emacs can make integrating with all window managers much easier. Again, most elements we need are already present:

- The window manager should provide some way to identify the active window class, and to move across and manipulate windows programmatically. This can be via a shell command, socket or server-based IPC, or (on Linux) via D-Bus methods. This covers most window managers and terminal multiplexers.

- On the Emacs side, we need a communication method-agnostic interface for window operations that mimics how most window managers do them, supporting a common subset of operations or (more ambitiously) their union.

- When switching windows in the window manager, we check if the active window is Emacs, and yield control to it if required. Emacs then performs the window operation within or without the Emacs frame as required.

As before, the missing ingredient is you!

The view from here

Believe it or not, this was the short version. To keep the scope of this piece under check, there are several window management strategies I had to exclude, such as anything involving tab-line-mode, or window types and properties like atomic, dedicated or side windows. And we are all safer for skirting around the issue of display-buffer.

Where does that leave us? With about a dozen ways to switch, move, jump around, create, delete and otherwise manipulate windows and window configurations in Emacs, many ways to control window display on the fly when invoking commands, and half a dozen ways to work across windows and avoid thinking about them at all. Once again, this collection is colored and limited by my experience with window wrangling in Emacs, and thus it’s not an exhaustive list. If I’ve missed something simple and useful please let me know!

For better or worse, window management in Emacs is not so much complicated as it is open-ended. Emacs provides the ingredients and some instructions, and the ingredients can work as basic meals by themselves.

But with a little cooking we can make something delicious. Bon appétit.

Updates and Corrections

Thanks to the following folks for corrections and suggestions:

- JD Smith for pointing out that

winner-modemaintains separate window configuration history per Emacs frame, so it remains viable if you use multiple frames. - Grant Rosson for reminding me that

pop-global-markdoes not work across Emacs windows by default, and needs a little advice. - u/simplex5d for corrections to the

winum-keymapdefinition. - kotatsuyaki mentions that

aw-dispatch-alwaysneeds to be set forace-windowactions to be available when there are two or fewer windows on the screen.